Ten years ago today, 14 September 2015, in the early hours of an ordinary American morning, an exceptionally strong gravitational wave chirp flew through LIGO‘s Hanford and Louisiana detectors, after having traveled across the Universe at the speed of light for something like a billion years.

Nobody (myself included!) was expecting it, even though almost certainly similar chirps had passed through the two detectors before, given that the detectors had been taking science data on and off since 2002. But this time was different, because LIGO was just restarting after a five-year-long major sensitivity upgrade. It hadn’t been sensitive enough to catch the earlier ones, but it heard this one loud and clear. The arrival of GW150914 therefore marked the dawn of gravitational wave astronomy as a new and promising research field.

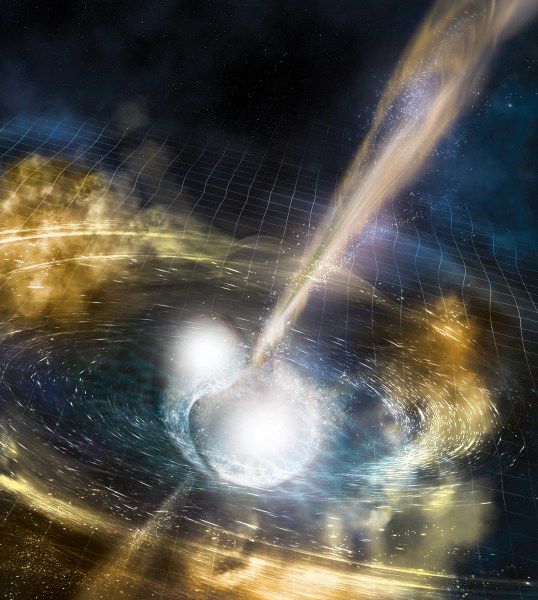

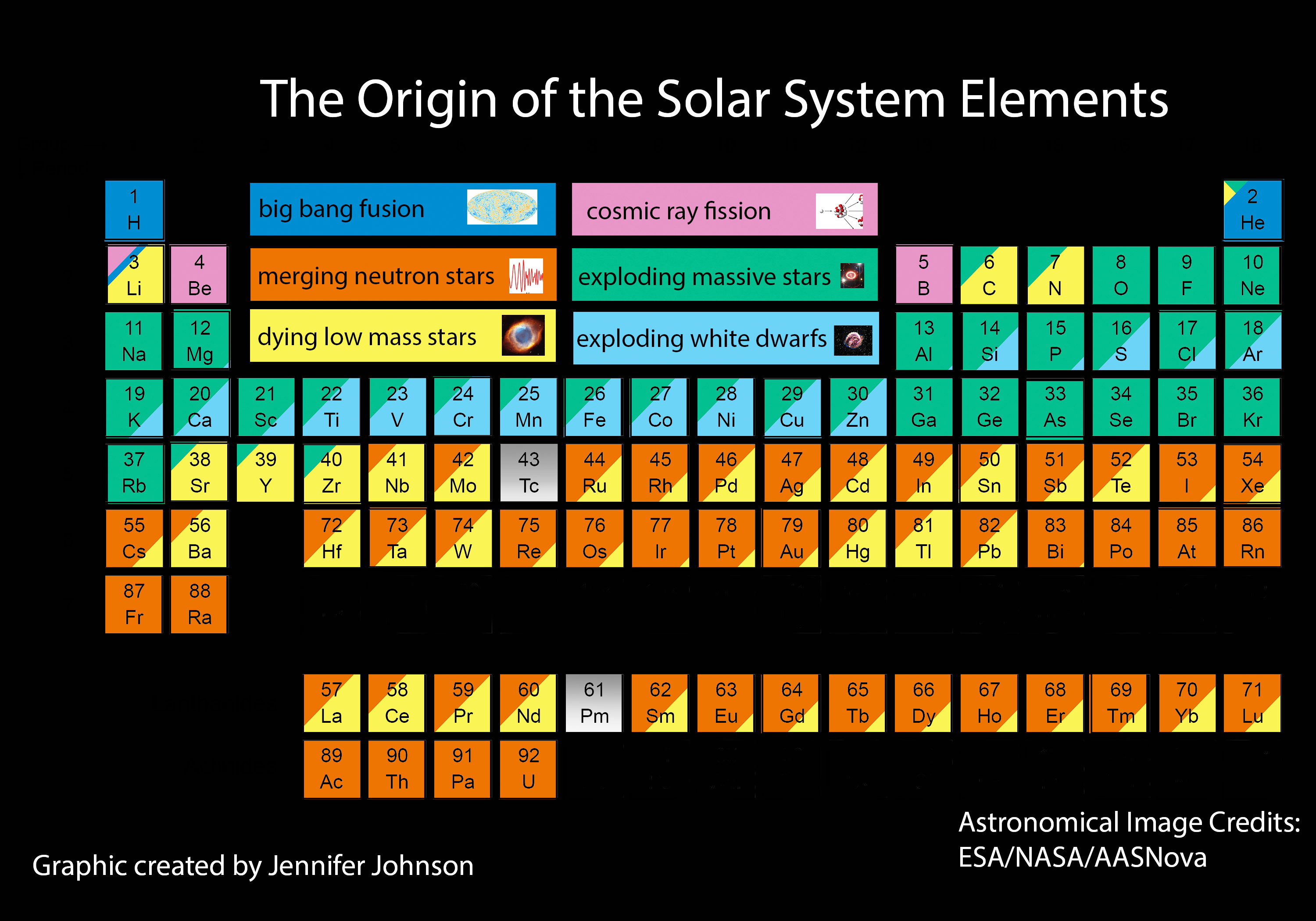

This first detection has been followed by well more than 200 further detections. Events are now being registered several times a week. Among the early detections was the profoundly important LIGO-Virgo observation of GW170817, in August 2017: two neutron stars spiraled together, merged, exploded, and taught us where our gold, silver, platinum, and uranium came from. This event led to a continuing collaboration of GW astronomers with other kinds of astronomers, something we call multimessenger astronomy. A few months later, the Nobel Committee confirmed the importance of this new field by awarding the 2017 Physics prize to Barry Barish, Kip Thorne, and Rai Weiss1.

During these ten years, a completely new way of detecting GWs has also made its debut: the pulsar-timing radio-telescope arrays have almost certainly detected a random cosmological background of ultra-low frequency GWs generated by the orbits of countless supermassive black hole binaries. This remarkable first decade of GW astronomy has brought us solid evidence, intertwined and in abundance, of the reality of all of Einstein’s theory’s most radical and unexpected predictions: waves of gravity, black holes, and Big Bang cosmology.

Naturally, the GW community is celebrating this anniversary. For my part, I am joining my good friend Clifford Will and many of our colleagues at a two-day meeting in Palma, Mallorca, which starts tomorrow. We will be looking backwards at what our community has achieved, and forwards at what we should be doing in order to keep this extraordinary momentum going. In this post, I want to muse about the future, because it has such promise and yet has to face possible pitfalls.

The LIGO and Virgo detectors are already significantly more sensitive than ten years ago. Further big upgrades are already being built and tested in labs around the world, in preparation for installation starting next year; the young Japanese KAGRA detector has an ambitious roadmap for improvement; India is building a third LIGO detector; and the space-based LISA gravitational wave mission is in Phase B of construction by the European Space Agency, having been handed over to the prime industrial contractor, on schedule for a 2035 launch. Into the 2040s we can hope for completely new third-generation ground-based detectors in Europe (Einstein Telescope) and the US (Cosmic Explorer), whose designs are already well advanced.

These upcoming instruments carry scientists’ high hopes for new science, unexpected or unpredicted discoveries. One remarkable and somewhat puzzling aspect of observations so far is that all the GWs detected so far originated from binary systems formed of black holes and neutron stars, whose brief death spiral emits a “chirp” of GWs and then falls silent, forever. Many other sources are expected, ranging from nearby asymmetrical spinning neutron stars emitting GWs continuously to distant exotic cosmic strings whose intense gravity emits a sharp burst of GWs when two of them happen to encounter one another. We apparently need even better sensitivity to detect the former; and we might just have to get lucky for the latter.

Future observations also should ultimately return the best-ever measurements of the expansion rate and acceleration of the Universe, values which are still a lot more uncertain than they should be. Their uncertainly lies in disagreements between values obtained by different methods, and I hope that the gravitational wave “standard siren” method will help resolve this, because it uses such different kinds of information than other methods rely on.

But all of this hope for the future is now hedged by uncertainties. One of the biggest is, of course, American political decisions about supporting science. We have seen devastating cuts in health research, including the halting of life-saving work mid-stream. The threats to space and ground-based science are also scary, although final decisions have not yet been made. There is talk of withdrawing NASA’s 20% contribution to LISA, as well as reducing LIGO to one detector, which would destroy its science return; LIGO itself has said it hopes that, if such a cut were made, then it could operate both detectors on a much reduced budget, presumably stopping the development of future upgrades and relying on university partners for keeping things going. We are hoping that Republican members of Congress will understand the importance of continuity in basic research and will vote that way, but the outlook is very uncertain. And that puzzles and distresses me, because besides being a Nobel-winning flagship for fundamental science — an endeavor that has captured large chunks of the public imagination –, LIGO and its partners have been wonderful training grounds for many hundreds of young scientists who eventually have taken their skills into industry. In the worldwide collaboration, they learned rigorous science, they learned how to push the frontiers of measurement time and again, and they learned how to work successfully and rewardingly in a huge international team. What could be better raw material for 21st century industry?

The other concern I have is that much of the future science return from our network, even if LIGO remains well funded, depends on having three detectors of comparable sensitivity, so that the sky positions of sources can be triangulated. With only two detectors, as we had for GW150914, we have big errors in the estimates of the masses and distances of sources, because our detectors have different sensitivity in different directions. We currently observe mainly with three detectors, the two LIGOs and Virgo. But Virgo has not been able to match LIGO’s sensitivity, typically observing with only 1/3 of LIGO’s sensitivity. This affects the number of events we can reliably detect, but even more it gives us poor direction-finding, which makes all the other measurements (masses, distances, spins) more uncertain. With time and with new contributions from KAGRA and LIGO-India, we can hopefully relieve this problem, but in the near term it stretches out the time it will take the network to reach any particular measurement goal, and makes the science output even more vulnerable to political issues over funding in the future.

Virgo’s problems do not come from a lack of talented scientists, although they may be a bit understaffed. Rather, it shows how incredibly difficult it is to build these instruments, so much so that small differences can have large negative effects. These are the most precise measurements ever made by humans, and getting within one-third of the best attempts is no mean feat. One of Virgo’s disadvantages was that it started ten or more years later than the teams that eventually merged into LIGO, and because of this they decided to go straight from the drawing board to the 3-km detector without operating an intermediate prototype stage for training and learning. But in my view, which I have expressed publicly on other occasions, there was another fateful decision at the time Virgo was organizing itself: it formed up as a collaboration of a number of research institutes, with no strong central management structure. It is led by a ‘spokesperson’, as is typical of particle-physics experiments, rather than by a ‘director’, which LIGO has, as do other successful European international science projects, such as ESA, ESO and the SKA. In fact, despite the heritage of the Virgo organizational model in particle physics, CERN itself also has a director, steering a strong management structure that has ensured that accelerator after accelerator has reached its design goal, making CERN the most important accelerator lab in the world. The Virgo organization model inevitably takes longer to make hard decisions, and design decisions can be weighted by inter-institute political and budgetary considerations rather than just by what is technically and financially optimal.

If this were a problem only affecting Virgo, then we could hope that with time it would get resolved, or at least would become less important as KAGRA and LIGO-India near their design goals. But the problem might run on longer than that: the next-generation European Einstein Telescope may soon receive its initial funding, but the organizational structure of its current collaboration looks to me to be just as decentralized as that of Virgo. As we look past 2040, there may again only be the two detector projects mentioned above for the third generation, and if Europe does not learn from the difficulties that Virgo has had to deal with, then it might endanger a truly golden chance to probe the Universe more deeply and more fundamentally than can even be conceived of today.

So as we celebrate what we accomplished ten years ago, I hope we will also learn lessons from the succeeding ten years about how we can optimize our research future … if the politicians don’t succeed in taking away that future!

- I dedicate this post to Rai, who passed away less than three weeks ago. LIGO was his conception, and he worked tirelessly for over 40 years to realize it. His modesty, mentorship, and good humor have strongly influenced the character of the worldwide GW collaboration. It is still difficult to process that he is no longer with us. ↩︎